‘Poetry For Our People’

“It’s poetry for our people, our community,” said David Tellyer, high school English teacher and Poetry Out Loud coordinator for Norton. “It’s students building confidence in their voices, their identities. And it takes all of us to build that. That’s what we’re doing here with Poetry Out Loud. Building a community for our school, our future. And who knows? We may even inspire other schools, other arts programs, along the way.”

Just a couple years ago, Norton had no Poetry Out Loud team and few fully-developed extracurricular arts offerings for middle and high school students. Instead, staff and students built programs with whatever they could muster. Newly-offered music classes had insufficient instruments to perform for school events, so they played ukulele and sang Christmas carols instead. When the new seventh grade English and drama teacher accepted another position halfway through the school year, an ambitious long-term substitute and teacher-on-assignment teamed up to have students perform scenes from “A Raisin in the Sun.” And Tellyer started a Poetry Out Loud club equipped with only printed out Poetry Out Loud performance rubrics, snacks for hungry performers, and a handful of passionate secondary students.

“That year we started out very easy, very slow, and very low-key,” Tellyer explained. “There were lots and lots of snacks, of course, to make students feel comfortable. Our goal was really to do the best we could with what we had and gauge student interest and commitment.”

Since then, each arts or extracurricular offering at Norton has worked to expand its opportunities and resources. A significant grant helped the music program buy instruments. Teachers trained in AVID started teaching AVID elective courses from middle to high school. And Tellyer guided Poetry Out Loud across the school campus–fifth to twelfth grade–recruiting more student and teacher involvement than ever before.

“This last school year we were much more serious, more intense, and more intentional,” Tellyer said. “We set competitive goals, we practiced thousands of hours, we recruited more students, we brought in more outside coaches, we got fifth grade teachers and students involved, we bought photography backdrops and lights, and we encouraged more parents and community members to attend our schoolwide competition in December. It was a massive organizational effort across the campus.”

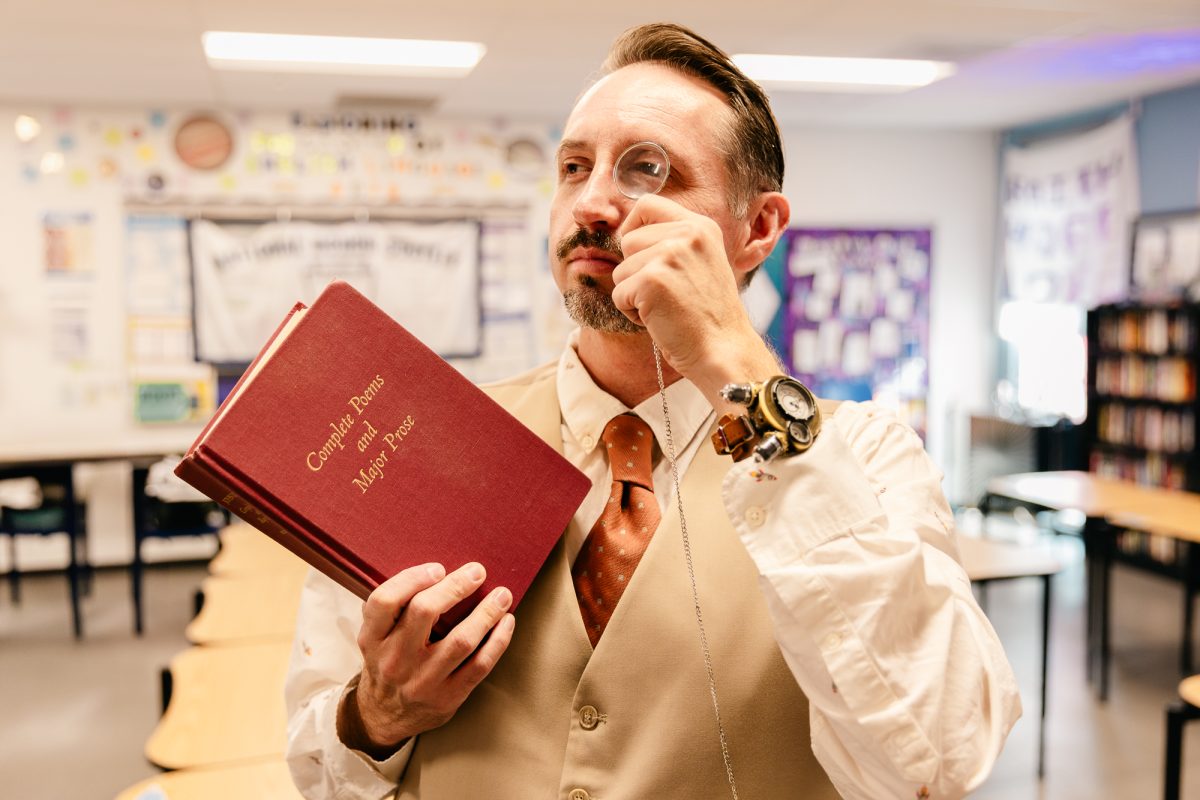

According to Tellyer, though, one of the true key purposes of engaging students with poetry is not to compete but to inspire, to change young minds. Like all literature, poetry can transform a reader’s perspective in some profound way that can then cause them to change the world around them. Tellyer, for instance, had an epiphanic shift when encountering a challenging canonical work of verse in college–”Paradise Lost” by John Milton.

“I became a teacher because of poetry,” Tellyer explained. “That’s one of the reasons why I have put so much time, effort, and resources into building our Poetry Out Loud program. When I started as an undergraduate at the University of California, Riverside I was studying neuroscience, a division of psychobiology–until I took a lower-division English course focused on John Milton. Prior to that course, I had thought of poetry as something enjoyable but not epic, life-changing. ‘Paradise Lost’ changed that. I started engaging with Milton’s work three hours each night, interrogating these epic symbols and imagery. The very scope of the work consumed me, enlivened me. Then, I started to research more about Milton’s philosophical ideas, and I found his essay ‘Of Education.’ In the essay, Milton describes education as the noblest pursuit and poetry as a catalyst for changing young minds. After reading ‘Paradise Lost’ and Milton’s essay about education, I was sold. I switched my focus to studying English literature. And I knew that I wanted to go into education, to teach young people and share the transformative power of literature.”

Now Poetry Out Loud is a staple of Norton, a cultural touchstone for the school that has grown exponentially over the last three years.

“We have really sculpted Poetry Out Loud into a pillar of community supporting our school. We made our first competitive attempt in 2022 with no real club or team, and we won second place in San Bernardino County,” Tellyer explained. “Then, in 2023, we really made an effort to build Poetry Out Loud into our campus culture and curriculum, and we won first place in San Bernardino County. That year every secondary English teacher included a unit for Poetry Out Loud and held an in-class competition using the Poetry Out Loud rubric. This last school year we featured even more competitors from every secondary grade level, practiced more and more intensely, expanded Poetry Out Loud to elementary school, hosted an even more spectacular school-wide competition in December, and won first and third place in San Bernardino County. And we are just getting started.”

Yet many might not understand the benefit of poetry recitation compared to other academic priorities. Certainly, some might say, Thomas Jefferson was right that the “three r’s” of reading, writing, and arithmetic are the foundational skills students need to meaningfully research political and economic issues and cast an informed vote influencing the trajectory of the United States’ political system. Not to mention, in 2023, United States test scores declined to the lowest levels in decades. Surely, then, these critics might contend, poetry is not as crucial as reading non-fiction about real-world problems or understanding the real numbers of an economic policy.

Critics might also point out that concerns with poetry in particular are not new. Poetry has been criticized for thousands of years for being an impractical pursuit or a fake representation of the world that deceives its audience. Famously, Plato critiqued poetry as mimesis, or an imitation of the real world. Through the dialogues of his character Socrates in The Republic Plato suggested that poetry, unlike philosophy, prevented people from getting to the truth of the world around them; instead, Plato thought, poetry distracted audiences with fake versions of the world that people could not rely on to make judgements about how to make the world better.

Skeptics of poetry’s significance may also rightly note that poets, too, have criticized their own artform. In her 1919 poem “Poetry” Modernist poet Marianne Moore writes: “I, too, dislike it: there are things that are more important beyond/all this fiddle.” Poet Darius V. Daughtry also reflects upon that trivial “fiddle” of poetry in his 2021 poem “what can a poem do?” Daughtry writes: “a poem cannot save a life…/a poem cannot delete history’s horrors.” Clearly, skeptics might emphasize, poetry does not have immediate and practical powers; it cannot perform surgery or stop climate change or elect national leaders.

But research on the positive impacts of arts education and extracurricular activities and the nationwide success of Poetry Out Loud challenge these long-standing remarks.

For instance, a 2012 report from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) found that students involved in arts education (either during the school day and/or as an extracurricular activity) were more likely to graduate high school, score better on standardized tests (including math and science), earn a bachelor’s degree, have higher overall letter grades, follow current events, vote in elections, read books for fun, and visit libraries. Similarly, a 2009 study found that students involved in extracurricular activities had a higher self-concept, stronger teamwork and leadership skills, and greater connectedness to their school community.

And Poetry Out Loud–the nationwide arts program in which students read, analyze, and perform poetry–has grown to nationwide prominence since its founding in 2005. In its second year of national competition, the 2006-2007 school year, Poetry Out Loud saw around 100,000 students compete. During its twentieth year anniversary, this 2024-25 school-year 157,000 students participated nationwide. And, since Poetry Out Loud launched, over 4.5 million students have participated.

Community, too, is an invaluable benefit for arts programs like Poetry Out Loud, and, in many ways, community is the tool that helps programs build, grow, and flourish. For Norton, that community looks like school staff sharing their enthusiasm about a literary art, teachers collaborating on poetry units across grade levels, students cheering on their peers’ successes, and community members uniting at school-wide events to support students. It is a recipe that other schools can learn from.

“What we’ve done with Poetry Out Loud shows that with a clear vision, pragmatism, and, most importantly, community you can truly build anything,” Tellyer said. “Any school can build something with the same faith, hope, and love. And that becomes infectious. Arts often get cut and sidelined for other academic programs, especially in less affluent schools, but they really are central to a school’s culture. And they help students become successful in so many other areas by virtue of the required work ethic, textual analysis, and public speaking skills practiced. Like all literature, poetry opens students’ minds and emotions to others’ experiences and more deeply into their own experience. It helps students have faith in themselves, hope for the future, and love for others and themselves more deeply.”

Or, as Daughtry’s poem later acknowledges, “a poem can love…/a poem can rip away the untruths that have cocooned us…/a poem cannot stop a bullet/but can swallow the hate and spit back.”

Poetry Out Loud really began to gain momentum a couple years ago during the 2023-24 school year, marking multiple historic firsts for Norton. All English teachers from grades 6-12 taught their own in-class units about poetry analysis and recitation. Students from each secondary grade level participated in in-class poetry recitation competitions. Norton hosted its first schoolwide Poetry Out Loud competition, featuring student performers from middle to high school. Then-freshman reciter Maximilian Goodly (‘27) won the San Bernardino County Poetry Out Loud Finals and competed for Norton’s first time at the California State Poetry Out Loud Finals in Sacramento. But, most importantly for the success of the Poetry Out Loud program, students met daily to practice their recitations with Tellyer.

Starting in October, students showed up each morning around 7:30 a.m., only an hour after the sun peeked over the verdant Loma Linda hills and overnight dew still frosted the stairway railings and campus planters.

Some students, like Dean Phelps (‘29), Luis Barajas (‘28), and Maximilian Goodly (‘27) showed up earlier than 7:30 a.m. and sat against the hall’s gray, stuccoed walls playing Nintendo Switch, reading a book, or listening to music.

But, when Tellyer arrived, students expeditiously packed up their individual sources of distraction and prepared for practicing something deemed serious and important–poetry.

“When Tellyer arrived, we knew it was time to work,” Goodly (‘27) explained. “It was only through that hard work I put in during the morning practices that allowed me to achieve what I did.”

“I practiced so hard because I wanted to feel the meaning of the poems I chose as I recited,” Phelps (‘28) said. “And I knew the only way to improve my performance enough to get to that level was through that dedication.”

Before making any performance choices, though, one of the first things students did to help them succeed was browse the 1,200 poems in the Poetry Out Loud database and select two poems that resonated with them thematically and stylistically.

For example, Maximilian Goodly (‘27) noted that even though poetry was not an interest to him prior to competing, selecting poems that connected to his interests allowed him to put his whole mind and heart into practice and performance.

“I really love the historical aspects of the poems I chose,” Goodly (‘27) explained. “The first poem I chose was ‘The War in the Air’ by Howard Nemerov. Nemerov’s poem is about a World War II pilot speaking on behalf of his fallen comrades in arms, other fighter pilots. And the second poem I chose was ‘The Battle-Hymn of the Republic’ by Julia Ward Howe. Howe’s poem is about the Union’s fight against the injustice of slavery during the Civil War. Both poems reflect my passion for learning about pivotal moments in history that shaped our nation. I do not think I would be able to perform as well if the poems were about topics I was less passionate about.”

High school reciter Elizabeth Son (‘25) also acknowledged how the poems she chose resonated with her interests.

“I found that I enjoy art that speaks to two universal human themes–love and suffering,” Son (‘25) said. “My favorite poem that I performed was ‘At a Window’ by Carl Sandburg. Both love and suffering are present in Sanburg’s poem. The narrator sits at a window longing for some person to give them comfort and support. They try to make a deal with fate, saying that they will accept a lot of suffering if they can just receive love from someone to support them through it. I think Sanburg’s poem reflects humans’ deep need for that kind of connection, and that really helped me put my heart into my performance.”

The next step was to internalize their selected poems’ meaning through hundreds of re-reads and make choices about how to perform their poems through hundreds, even thousands, of practice recitations.

“Before I could even get to that point of pride in representing my school at a school competition, I had to recite my poems until the words echoed in my brain while I slept,” Goodly (‘27). “And I had to think about how to make each gesture or movement count. As Tellyer told us, the focus is really the words and meaning of the poetry, not the drama of our movements. It is important to really reflect the message of the poem so that an audience of strangers can focus on the poetry, not just what I’m doing.”

The final step to perfect their performances was to recite before large audiences of friends, family, and, indeed, strangers at the schoolwide, countywide, and statewide levels.

“Of course I was a little nervous at first competing in front of the school then county then state. Not to mention, it was the first time for us presenting in front of the entire school and moving on to the state level, too, which was a huge deal,” Goodly (‘27) explained. “But if you’ve really practiced your performance, it becomes like muscle memory. You’ve planted the connections mentally, emotionally, and physically with your poem, you’ve watered the poem inside your brain, and now that poem is ready to flourish like your own little plant. If you do the work, the work will do things for you.”

That hard work at early-morning practice sessions paid off. At Norton’s first-ever schoolwide Poetry Out Loud competition on Thursday, Dec. 7, 2023 Son (‘25) and Goodly (‘27) placed first and second for high school. And Phelps (‘29) and Barajas (‘28) won for seventh and eighth grade.

“We made history at that first school competition,” Tellyer said. “During and after the school competition we kept getting told, ‘All schools should have events like that.’ Parents and family members said they were impressed with what students memorized and performed.”

“After that first schoolwide competition, I was exhilarated,” Goodly (‘27) remarked. “I didn’t end up winning first place then, but it was incredible to showcase something I had worked so hard on to my family and friends. Then the next week after the competition I went back to practicing, day in and day out, until the county competition. And at the county I really put everything into it. I think I gave one of my best performances to date, and that helped me move on to the next level.”

After taking first at the San Bernardino County Poetry Out Loud Finals, Goodly (‘27) went on to compete at Sacramento at the 2024 California Poetry Out Loud Finals. Ultimately, though, he did not place at the state level. Still, Goodly (‘27) acknowledged that the state finals were an invaluable opportunity and priceless learning endeavor.

“State was an absolutely breathtaking experience,” Goodly (‘27) said. “I had never been to the capital of California. I had not been to Sacramento. So getting the experience to actually go there, see the capital, and compete [made me feel] I was in a competition that was much greater than myself. It was daunting at times, just the immense scale of it, but it was extremely gratifying to make my parents and teachers proud.”

Tellyer added that seeing the huge growth of the Poetry Out Loud program–from school to state level in a single year–was crucial to building community support and enthusiasm. And it helped him learn what strategies to implement the following year.

“We practiced really diligently that first serious year of doing Poetry Out Loud,” Tellyer said. “That was honestly our biggest success–having dedicated students practice, practice, practice. That commitment to the process built our community, made others take us seriously, and helped us do well at the competitions. But we learned that we needed to change up our style for each competition level, and we needed to recruit even more students and coaches.”

Goodly (‘27), too, reflected that his hard work and achievements were a foundation on which to build in future years.

“I hope to return to state level again and apply all the new strategies and skills we have learned as a Poetry Out Loud program to my performance,” Goodly (‘27) said. “We have learned so much from what we have done since that first year that I think we can keep reaching new heights.”

Last school year, 2024-25, Poetry Out Loud grew from a fledgling program that had achieved some initial success into a larger-scale community program that incorporated fifth to twelfth grade, multiple coaches, multiple parents helping their students practice recitation at home, and multiple student performers participating at each grade level.

“We pulled out all the stops,” Tellyer said. “We took our shortcomings from last year and set new goals. That is a huge lesson for any school program–keep trying to beat your school’s personal best. For example, last year we got enthusiasm from elementary teachers who were saying ‘This is something that we want to do.’ And so this year we got fifth graders analyzing, memorizing, and performing poems in front of hundreds at our schoolwide competition.”

Fifth-grade teacher Lilia Avila shared what it was like to get her students involved.

“It was powerful to get my students interested in poems by Langston Hughes and Emma Lazarus,” Avila said. “We read Hughes’ ‘I, Too’ and Lazarus’ ‘The New Colossus.’ Then we analyzed what they’re trying to say about people’s dreams and aspirations in America. I also shared poems by young poets like Amanda Gorman and bilingual poets like Rhina Espaillat. Even though Poetry Out Loud resources were more intended for secondary, we were able to adapt their materials and make it work well for our younger students. After students selected and analyzed their poems, we held an in-class competition, just like secondary. What struck me, again, through this process was that students were identifying more deeply and passionately than the year before when we read these poems for the same unit. They were now thinking about how they could put themselves into a performance of the poem as we were reading them as a class.”

Avila’s words matched the energy from her students. For instance, fifth-grader LauraBelle Goodly shared how she found personal meaning in “The New Colossus,” a poem that Lazarus originally wrote to fundraise for the construction of the Statue of Liberty but that has since become emblematic of the immigrant’s journey to the United States.

“The way I related to the poem was through my family’s history,” Goodly explained. “Over hundreds of years, my family came from a lot of different places. Some of my family had to escape Colombia. Some of my family had to escape unfair slavery. But they all ended up in America, striving to build a better future for their families and generations after them. And I think that is the heart of the poem–that people can fight to be seen and heard in America, no matter their position in life.”

Fifth-grader Samantha Lara also connected to “The New Colossus,” but devised a slightly different meaning.

“I liked how the poem focused on helping those facing challenges or those with less opportunities,” Lara said. “It felt like Lazarus was saying that our people, our country should never give up in the face of challenges. The way Lazarus talks about ‘us’ and ‘we’ together makes me like I can face my own struggles, too.”

Avila observed that it was refreshing to see students make their own meanings out of the same poem.

“Even though many students read and recited the same poems, it was rewarding to see how they brought their own meaning and interpretation to it,” Avila said. “It showed that there are many American Dreams, like our in-class unit was about. But it also showed me that a poem can speak differently to different people, and, as a result, that poem can be spoken or recited differently by different people.”

Avila noted, though, it was, at first, a challenge judging subtle differences between students’ poetry performances.

“Not everything was straightforward as we did Poetry Out Loud for the first time,” Avila explained. “When we did the in-class competition, we actually had four first place winners. I had to call in middle and high school students that had rehearsed with Tellyer to help. The secondary students helped me look at each competitor’s use of vocal emphasis and gestures, really reflecting on the small differences between the performances, and then, after that mental work, we decided the top places. It really helped me more deeply understand the expectations for Poetry Out Loud, and it showed me how the secondary students had so deeply understood expectations for poetry performance that they could then teach others.”

After the in-class competition, Avila pushed students to practice reciting every day using the Poetry Out Loud rubric leading up to the schoolwide competition in December.

“Tellyer and the secondary students had set such high expectations that we wanted to honor that hard work,” Avila said. “We wanted to make them proud. So everyday we spent time going over the rubrics, going over students’ recitations.”

Goodly shared how practicing over and over again made her realize what she needed to add or change.

“Ms. Avila told us first and most importantly to truly make the poem our own,” Goodly said. “She said that we should not pick a poem just because it is short and easy to remember. And we should not recite in such a way that makes the poem feel empty or meaningless. She really made it clear that we need to put our heart into it. She also encouraged us to practice at home, so, with help from my mother, I got a tall mirror and practiced in front of it thinking, ‘If I was an audience member, what would I want to see in the person performing? Would I want to see them be timid, hands glued to their sides, or adding emotion and intention through the poem, through tone and movements?’ That made me understand how adding hand movements can communicate the meaning of the poem, rather than distract from it.”

Lara echoed many of the same lessons learned while intensely and intentionally practicing.

“Ms. Avila started coaching us based on the rubric each day,” Lara said. “She told us it would be easiest to recite and memorize our poems if we started practicing outside school, too. So I began to practice reciting ‘The New Colossus’ whenever I got the chance–in the car, after I finished my homework, during breaks from sports practice. My parents just kept saying that I could do it and that I could keep improving. They also helped me decide what gestures I should do with my hands to show the meaning of the poem. After I did that for a week, it felt easy to recite–and it boosted my confidence performing in front of others.”

And, despite students not having yet performed at the schoolwide competition, Avila already noticed a change.

“Students started realizing they were using their voices and presence in a way they hadn’t even thought of before,” Avila said. “They realized that they had no reason to be nervous, that they could communicate confidence by the volume of their voice, their body language. The process of practicing helped them realize more about themselves and what they had to offer the world.”

There is not one correct way to connect with poetry. Reading is one way to experience stanzas, rhymes, and emphasis. But writing–the act of creation–makes one consider how and why poets write what they do. Writing makes poetry personal.

“We wanted students to try writing their own poetry as part of the creative process,” Tellyer explained. “We wanted to see if the act of writing helped them choose and analyze poems more authentic to themselves.”

Some English teachers, like Melissa Maldonado, took up that challenge of teaching students how to write poetry of their own before selecting and analyzing poems from the Poetry Out Loud database.

“I wanted students to write their own before choosing one from Poetry Out Loud because many students had a preconceived notion that poetry is boring and unrelatable,” Maldonado explained. “Challenging students to create their own poems pushed them to realize that poetry, like any creative work, is something personal. First, I had students learn about poetic elements–like rhyme scheme, emphasis, repetition–then I had them make their own flip-books with a definition, picture, and original example. Next, I had them annotate poetic elements in five different free verse poems. Some of those poems included ‘Still I Rise’ by Maya Angelou, ‘Stupid America’ by Abelardo Delgado, ‘I’m Mexican’ by J. Arceo, and ‘Latino Americano Children of an Oscuro Pasado’ by Xochitl Morales. I chose these poems because they emphasized personal identity and made students reflect on what it means to belong to a culture, a history, a family expectation, but also become yourself. Lastly, I had students write their own poems to read for our own coffee-house-style open mic during class. I wanted students to see each other present as writers and feel what it is like to be open and personal in front of an audience. I even wrote my own poem to model what it looks like to be vulnerable and authentic in writing.”

“Mis padres come from humble beginnings/Mamá only finished second grade and Papá only finished 9th,” Maldonado shares in her poem “The First,” “But being the first is not always rainbows and butterflies, oh no/Because I am the first with a mind that is a recurring tornado storm/The first having to pull all-nighters just to complete projects and quizzes/All the endless night, stressed and crying…Mi ma y pa dreamed of a first like me/So although I struggle, it is a struggle que estoy contenta de hacer, because I am the first/To achieve their dreams.”

Maldonado explained that her own poem was inspired by her journey as a first-generation college student.

“I have had the honor to accomplish my parent’s wildest dreams,” Maldonado said. “But it does come with a lot of stress and pressure to be great and not fail. I wanted to write a poem that encapsulated that constant tug-a-war feeling that many first-generation students feel, especially because I had to navigate a lot of it on my own. I hope the genuine parts of myself I put into the poem motivate students to take risks in their own poetry and educational journey.”

In the process of writing their own poems, students also pushed each other to take poetry more seriously.

For instance, one of Maldonado’s ninth-grade students, Zayhier Hodges (‘28) said that he was not taking writing his poem seriously until he saw a classmate putting so much effort into theirs.

“I saw my friend Miley working so hard to write her poem and being so genuine in her words that I was kind of embarrassed at what I had written,” Hodges (‘28) said. “After seeing her poem, I started over with a completely different idea. I wanted to write about something that I had gone through–others taking advantage of the kindness and support I had given them.”

“How does it feel/knowing that a thief can come and steal your peace/because your lack of boundaries gives them permission?” Hodges (‘28) writes in his poem “Boundaries,” “No excuse should excuse you from not putting yourself first/What, you scared of your past or something?…/‘Cause what you feel is what you attract…/So take back your peace/Let boundaries be clear/And bask in the light/Of all you hold dear.”

“The poem was both a statement to myself and those who caused hurt,” Hodges (‘28) explained. “It is about how boundaries are a two-way street. That my own self-worth and mental health requires guarding limits to how much of myself I give over to others.”

Maldonado discovered, like Hodges’ (‘28) admitted, that many students began to see more value in poetry once left to grapple with the task of writing something original and expected to work as hard as their peers surrounding them.

“After students wrote their own poems and performed them, they were much more open to choosing poems from Poetry Out Loud,” Maldonado concluded. “They understood more the point of poetry–to be creative, vulnerable, and true to one’s self. I saw them become more thoughtful about what poems they picked and why. Writing helped them think and feel more deeply about poetry.”

Robert Burns’ 1785 poem “To a Mouse” famously notes, “The best laid schemes o’ Mice an’ Men/Gang aft agley.” Burns’ words translate to mean in more modern English wording, “The best laid plans of mice and men/Often go awry.” Those well-known lines from Burns’ poem suggest that wisdom is simply accepting that things can go wrong in unexpected ways.

But students’ efforts on the afternoon of Norton’s school wide Poetry Out Loud competition, Thurs. Dec.5, 2024, suggest something a little different–that true peace is found in addressing challenges, not just accepting that they happen.

“True community prevails through obstacles,” Tellyer said. “And that’s exactly what happened the day of the schoolwide competition. So many of my responsibilities and deadlines were piling up. It just felt like a huge boulder I had to carry to the top of the mountain, and I knew I could do it, but it was still overwhelming. Then, during my last section of the day, my twelfth-grade English class, a student had a medical emergency, a seizure that left them seemingly catatonic. I was worried the student might not make it–that something was seriously wrong. And I just felt like I was going to drop the boulder, and there were so many people counting on me, expecting things from me. We were going to start setting up for the schoolwide Poetry Out Loud event during this creative writing class–the competition that was going to start in just a couple hours afterschool. We had worked so hard up to this point–teaching poetry analysis, practicing with students, giving feedback, training before and after school, getting other teachers on board. But there was still so much to set up and double-check–microphones, stands, lights, backdrops, chairs, snacks, signs, posters, tables, presentation slides. And the incident just shocked me and I froze and I felt like I could not lift the boulder anymore and I was going to disappoint everyone. Then, in that kind of frazzled state, I said to the students, ‘Call a Campus Security Officer.’ And students jumped into action.”

“It was students that took the lead,” Tellyer detailed. “I was kind of giving directions in a daze, working on teacher autopilot. But the class helped get the student to a safe place while others ran out and called for help. Then, those from my class clearly explained what had happened to the security and health staff. The paramedics and ambulance arrived, and the student was taken to the hospital.”

“After the sirens faded out and the class was sitting back in their desks, I just sat there very worried and overwhelmed. I care about all my students and to see a student of mine go through that was extremely troubling,” Tellyer admitted. “And then my mind went back to all the set up and double-checking that needed to be done, and I just felt like I couldn’t move from the pressure. Students had to ask, ‘Hey Tellyer, are you OK? What do you need?’ And I told them, ‘I need the show to go on. I need this poetry event set up.’ And students actually listened and went to the multi-purpose room to start.”

“My twelfth-grade English seniors, Poetry Out Loud competitors, creative writing students, seniors on leadership committee, Associated Student Body all started helping set up. They took the basic directions I gave them, they recruited help from other teachers and staff, and they set up,” Tellyer said. “When I walked into the multi-purpose room, it was perfect. It was just how I envisioned it. The atmosphere felt welcoming, ambitious, celebratory. My students, my school, my poetry community helped carry that boulder up the hill when I thought I was going to drop it.”

After everything was set up, the doors opened. Hundreds of teachers, friends, family, classmates poured in. No chairs were left–it was standing room only.

“We were expecting more people than last year,” Tellyer remarked. “But the turnout was tremendous. It was more than we could have wished for.”

Then the event started, and elementary reciters made their debut onstage.

Looking out into the crowd, spotlight glaring, Goodly felt determined to show what an elementary student could accomplish with enough hard work.

“My brother, Max, had competed at state last year, so it felt important that we represent elementary and show what we can do, too,” Goodly said. “I trained everyday before the school competition, so when it was my turn to step on-stage I felt giddy and confident. I felt giddy because I had been training and waiting for that amazing moment for so long, and now it was standing before me. And I felt confident because I knew that I had ticked off every checkmark and had the requirements to deliver a satisfactory performance.”

Next, Lara walked out, excited to share, ready to face any lingering anxiety.

“I felt shy, nervous, and excited because I was performing out loud to my family and friends,” Lara said. “I felt shy because there was a giant crowd and there were so many people that there were not enough chairs. Some had to stand or sit on the floor. I was nervous for the same reason, and I even accidentally kicked a speaker that was right in front of me. But deep down I was truly excited because I felt like I made a big achievement to show off what elementary students can accomplish. I also wanted the audience to feel the emotion in my poem ‘The New Colossus.’”

Then the secondary reciters took the stage one-at-a-time, delivering the performances they had poured hours into rehearsing, for two back-to-back rounds of recitation–one round for each poem, just like the structure of the state and national Poetry Out Loud competitions.

“Before it was my turn to face the crowd, significantly larger than last, I did feel nervous,” Goodly (‘27) said. “Everyone was packed into the audience, students and teachers were all fixed on the performers, watching every moment and syllable emphasized. There was an air of ‘This is an important moment for our school–history is happening here.’”

“Last year I just completely crumbled at the schoolwide competition,” Samsylvanus (‘28) said. “But I stepped onstage knowing how much harder I worked, how much improvement I had made. And I told myself, ‘You can’t get lost in your head. You can’t get nervous. Just think of the poem.’ I just wanted to focus and see how far poetry could take me. I wanted to make my family and school proud.”

After secondary concluded both rounds of their performances, the panel of judges conferred in hushed tones, comparing annotated rubrics, reflecting on students’ body language and vocal resonance. And, finally, they announced the secondary winners that would move on to the countywide competition in January–first place champion Maximilian Goodly and runner-up Toochi Samsylvanus.

Applause burst out from the audience, friends and family of competitors cheered, cameras flashed lights and snapped shutters to document the occasion.

“It was a triumphant moment not just because of how hard students practiced but also because of how we came together to set everything up that day,” Tellyer reflected. “And, luckily, we later found out the student was okay after their medical emergency. We can look back and think about how it was inspiring that our community addressed such a stressful moment. We were committed to helping a student in their time of need and getting these students onstage to do their best.”

But, after any school’s campuswide Poetry Out Loud competition, the work is not done–at least, if students want to continue competing at higher levels. Like any artform, to truly perfect a poetry recitation, practice really does make perfect. Thousands of hours of practice. Feedback from multiple coaches across multiple weeks. Stress, sweat, tears–and then, after failure and feedback and focus, some success.

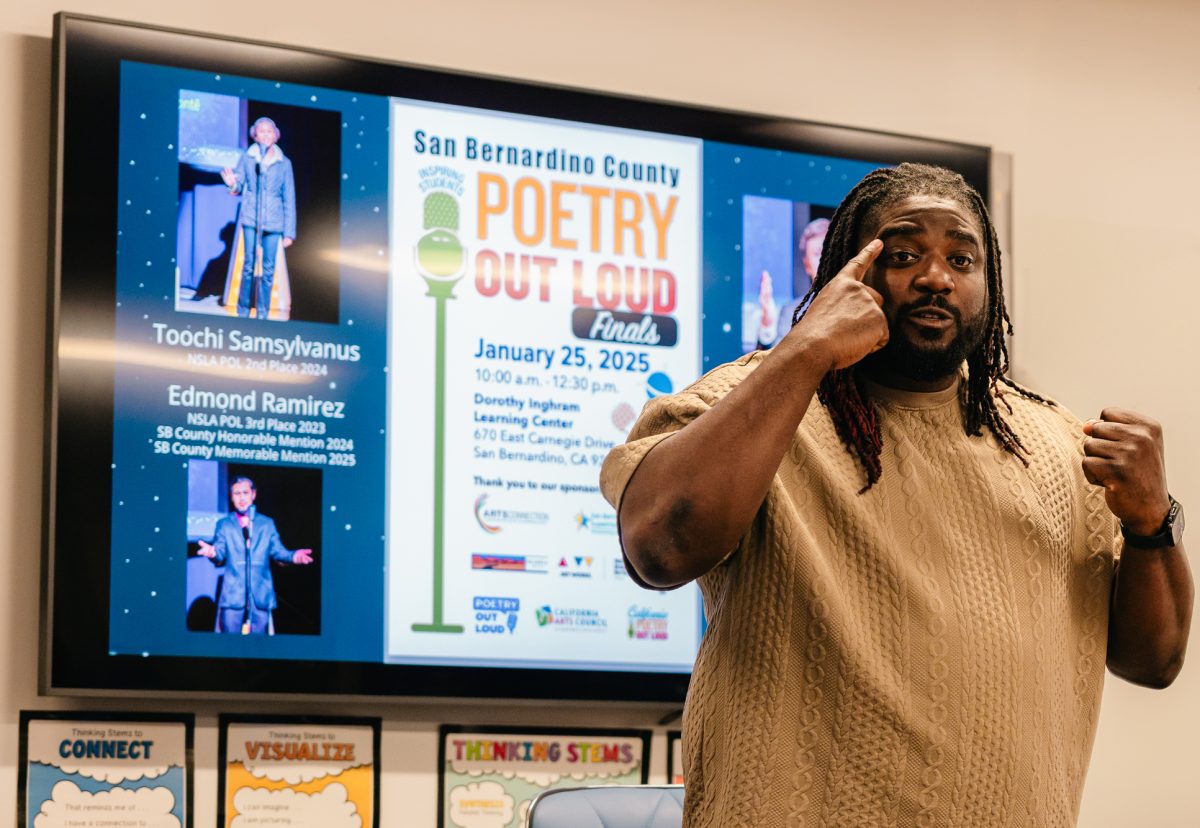

Goodly (‘27) and Samsylvanus (‘27) put in that work, addressing notes from new coaches, like Romaine Washington and Brandon Allen, to prepare for the county level.

“We asked Washington, a local poet and retired high school English teacher, and Allen, another local poet with a profound story and commitment to helping young people, to coach and give feedback to our two student competitors moving on to the county,” Tellyer clarified. “We wanted to really learn from as many experts as possible and connect with the local poetry community, too. After all, we are trying to build something larger than our school.”

Students noted that one of the main pieces of feedback from both Washington and Allen was to focus on pacing, enunciation, and vocal emphasis, not overdo it with theatricality. As Washington writes in an op-ed about the value of students reciting, “Is [Poetry Out Loud] slam poetry? No. No props. No singing. No slam.”

Most Wednesday mornings leading up to the county competition, Samsylvanus (‘27) and Goodly (‘27) worked before school in Tellyer’s classroom to receive constructive criticism over video calls from Washington–with a dose of support and reassurance.

“Ms. Washington was very nice and supportive,” Samsylvanus (‘27) said. “But she was very serious and passionate about helping us improve. If I was not enunciating a word correctly, she let me know.”

“It was clear she wanted us to do our best,” Goodly (‘27) added. “But, yes, she did give us feedback that was challenging at first to work on.”

“I start coaching sessions in a very straightforward manner,” Washington explained. “I ask the student to recite the poem. Sometimes I will model pacing or emotions for them to hear the poem from a different perspective. If I feel there is a disconnect in certain areas where I think the student isn’t completely engaged with the words, I will ask them what certain sections mean and if they are feeling what they are saying. Emotionally connecting with the poem is crucial–and I don’t mean acting it out. I mean completely connecting with the words and intent of the poem.”

Samsylvanus (‘27) and Goodly (‘27) reflected on some elements of their recitations they workshopped with Washington.

“She told me to really slow down and work on emphasizing the opening lines of my first poem by Emily Brontë,” Samsylvanus (‘27) continued. “I had to work on enunciating the line, ‘Shall earth no more inspire thee.’ I was kind of just rushing over it at first. For some reason, I had a hard time doing that–it took me a while to really work on saying each word’s sounds completely.”

“I was told that I needed to add more emotional depth to my recitation of my first poem, ‘The Anthem for Doomed Youth’ by Wilfred Owens,” Goodly (‘27) said. “That was hard to hear at first because I thought I was connecting with it. But then I thought more about family connections I could have to the topic of war and grief and tried to bring those emotions into the words I was saying. I first imagined what it would be like for the narrator of that poem after World War I, lamenting the deaths of friends and family members, and then I thought of a personal connection, family I had recently lost, like my grandma and aunt. It made me appreciate how the poem was conveying this deep sadness but also reverence for what someone accomplished, just like how I felt about losing a family member that did so much for me.”

Allen also came in to motivate and give feedback.

“I want you to really think about how you connect with the poem,” Allen said in a presentation to all secondary Poetry Out Loud students during homeroom. “You should not sound robotic or monotone. Put your passion in there. Then, you can work on each word, each line.”

“At a certain point, I had the honor to meet and work with Mr. Allen. I started working a lot more with him, and Max worked more with Mr. Tellyer and Ms. Washington,” Samsylvanus (‘27) explained. “Mr. Allen made me consider why I gravitated toward the poems I chose and what story or connection I had with them. I reflected on how Brontë is talking about courage and believing in forces larger than yourself, and I felt like I could connect that to wanting to live up to the expectations of my family. He also showed me a different approach to practicing enunciation. He gave tongue twisters to repeat over and over again to make me realize how certain vowel and consonant sounds require extra pause. He would have me say these nonsensical phrases like, ‘I love New York, unique New York, I love unique, New York,’ and it took me a bit to not stumble over the last time I say ‘New York.’”

“I kept working with Mr. Tellyer and Ms. Washington,” Goodly (‘27) added. “And we focused more and more on how to better enunciate or emphasize certain words and lines. In ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’ they suggested I make the line that says ‘stuttering rifles’ rapid rattle’ sound more like the quick gunfire the line is describing. In my second poem ‘The Statesmen’ by Ambrose Bierce I had to look up and work on some of the older language in the poem like the ending word ‘vermifuge.’ When I first read that, I thought, ‘What the heck is that?’ I had to look it up and decide how I wanted to say or emphasize that word.”

Then, after such in-depth practice and revision, it was time to face this year’s county competition.

On the cool, crisp morning of Saturday, Jan. 25, 2025, Norton staff and students went out to support Goodly (‘27) and Samsylvanus (‘27).

“I felt like we had such hard working and impressive reciters this year heading into the county,” Tellyer said. “And, just like in December, many staff and students showed up to support, even though the event was on a Saturday.”

As they sat in their chairs in front of the microphone, Samsylvanus (‘27) and Goodly (‘27) worked to stay calm, mentally locking in to the words and pauses and emphasis they had branded into muscle memory.

“As I was sitting down, I was really nervous, I was almost shaking,” Samsylvanus (‘27) said. “But I practiced breathing in and out, in and out. Then, I got called up and I just put my mind toward the words and the emotions I had practiced with each line.”

“I was ready but felt the usual wavy feeling in my stomach before I went up. I knew, though, that as soon as I got into reciting the poem that’s all I would think about,” Goodly (‘27) said. “It’s like everything else melts away after you’ve worked to recite the same poems over and over again.

Just like the schoolwide competition, Goodly (‘27) and Samsylvanus (‘27) recited for two rounds back-to-back. This time, though, they faced students from several different local schools–Big Bear High School, The Grove School, Granite Hills High School, and Upland High School.

“It’s always interesting to watch the other students recite and consider how and why they made the choices they did in their performance,” Goodly (‘27) reflected. “It makes you think more deeply about your own presence onstage.”

At long last, after both rounds of watching and performing, the county results were revealed–Samsylvanus (‘27) took first and Goodly (‘27) took third. Cody Edwards from Big Bear High School took second.

“I wasn’t expecting to win,” Samsylvanus (‘27) said. “I didn’t believe it at first. I thought they were going to announce Max or the student from Big Bear, not me. It took me a moment to realize that, no, they actually meant me. Then, I got up and had to shake everyone’s hand, still shocked.”

“I did expect that I would do better,” Goodly (‘28) concluded. “But I was so happy that Norton took first. I was glad that we would get to represent our community again at state. And, of course, I learned a lot that I can continue to apply to my recitations next year.”

After Norton’s success at the San Bernardino County Poetry Out Loud Finals, Norton received praise and accolades and encouragement from many different places.

“Norton is now considered a Poetry Out Loud Demonstration School for San Bernardino County,” Ulises Rodriguez, Associate Director of Operations & Programs for The Arts Council of San Bernardino County, said. “That means that we want other schools to look at the culture celebrating poetry here and learn from it. Norton has the chance to lead by example.”

Norton also gained recognition from the San Bernardino Superintendent of Schools, Ted Alejandre. At the San Bernardino County Board of Education (SBCBOE) meeting on Feb. 10, 2025, Alejandre noted the performances from Norton students at the Poetry Out Loud county competition.

“We had our third annual Poetry Out Loud event. This was the biggest one we’ve had so far,” Alejandre said. “The students who were involved in poetry did a tremendous job. And our two winners from Norton Science and Language Academy were phenomenal.”

Norton staff and students also congratulated the winners in the halls.

“It was so strange,” Samsylvanus (‘27) said. “People were coming up to me and saying, ‘Congratulations’ and ‘Good job’ even though I don’t even normally talk to or hear from them. It was like I was famous for a day.”

“There was such electric energy knowing that we were having the opportunity to compete at the state level once again,” Tellyer said. “It was rewarding, too, to see so many people congratulating our student winners. We had brought Poetry Out Loud to everyone’s attention enough to make them go out of their way to celebrate it. Now we just need to keep up our cycle of practice, like we did before the county.”

For Samsylvanus (‘27) now that routine of practice and revision was like clockwork. It was, instead, a way to pass the time, a routine like sports or music practice that connected the days into weeks and weeks into months.

“It felt like I had just performed at the county,” Samsylvanus (‘27) said. “And then it felt like all of a sudden we had to get ready to fly to the state capitol. It was like we were time traveling ahead. The main difference was that now I was practicing my third poem, ‘a song in the front yard’ by Gwendolyn Brooks.”

“The challenge with my last poem was that it had such a different flow than my first two Brontë poems,” Samsylvanus (‘27) said. “So I had to adapt. I kept working with Mr. Tellyer and Mr. Allen on how to adjust to the rhythm of the lines that kind of ran over into the next without necessarily pausing.”

Even with additional practice, the time to fly to Sacramento for the 2025 California Poetry Out Loud Finals came quick. And soon Tellyer and Samsylvanus (‘27) and her mother were soaring over farms, mountains, and California coastline to the capitol.

“It felt kind of surreal flying over everything to such a huge event,” Samsylvanus (‘27) said. “It was like a movie, a dream.”

After she touched down and walked up the steps to Sacramento’s Memorial Auditorium and into the Jean Runyon Little Theater, though, Samsylvanus (‘27) reflected.

“No matter what I already won,” Samsylvanus (‘27) said. “I’m here with thousands of people, probably almost a hundred other students reciting, and my mom and Mr. Tellyer are here to cheer me on.”

But, unlike the school and county competitions, there are two separate days of recitation at the state finals and students must recite all three poems, one poem the first day and one poem the next. The number of participants is also significantly different. On the first day one student from every county all over the state performs onstage back-to-back. The next day, everyone performs again, and the average scores from both days are calculated for each reciter. Only the top five students make it to the third round on the second day, and they recite their third poems.

Samsylvanus (‘27) was one of those students.

“It was so thrilling. We reached a new achievement,” Tellyer said. “We had made it to the third and final round of state.”

The last day of the finals Samsylvanus (‘27) proceeded to the State Capitol Annex Swing Space, a building whose interior more resembles an austere board meeting room than a performing arts space.

“It felt more official and serious than the theater we were in the day before,” Samsylvanus (‘27) said. “It was a little intimidating.”

After all attendees nestled into the annex’s plastic-backed meeting chairs, the process repeated–with every county champion from across California.

“Of course I was anxious to see what would happen,” Tellyer said. “But the only way forward is to give affirmation after affirmation to those you are supporting. Think positive.”

Finally, after hours of recitations came the deciding moment-first place champion Selah Johnson from the Archer School for Girls in Los Angeles, second place runner-up Toochi Samsylvanus (‘27) from Norton, and third place honorable mention Madeline Chiu from Vintage High School in Napa.

“I don’t want to say it was luck,” Samsylvanus (‘27) said. “But it certainly felt unreal and even relieving, like my hard work had finally paid off as much as it could.”

At Norton, some staff and students watched the state competition live online in class, cheering and clapping as the results were announced.

“When I got back to Norton, classmates were already telling me they were proud of me, and I was like, ‘How do you know what happened?,’” Samsylvanus (‘27) said. “I didn’t think anyone would be watching it live like a lot of the English teachers had done with their classes.”

After award-giving and picture-taking was complete, Tellyer, Samsylvanus (‘27), and her mother packed back into a car, packed and ready to head to the airport.

“We were driving back to fly home, and then I got this phone call,” Tellyer said. “And they were asking, ‘Wait–where are you? Come back, they want all the winners to go to the state senate.’ So we turned around. Apparently, Senator Allen wanted to honor the day as the anniversary of Poetry Out Loud with a bill. And he wanted all the state winners to represent the poetry program in front of the California Senate.”

Johnson, Samsylvanus (‘27), and Chiu then all entered the state senate building, surprised and excited, before being invited onto the senate floor to commemorate the passing of California Senate Concurrent Resolution 31 that commemorated May 17, 2025 as the 20th anniversary of Poetry Out Loud.

“It was a profound way to end our experience at the state,” Tellyer added. “It was a historic moment for our school, and it was a historic moment for the history of Poetry Out Loud. It felt like it was meant to be.”

Upon return to Norton, there was celebration for Samsylvanus (‘27)– more cheering and congratulations from teachers and students, lunchtime banquets in her and the program’s honor, and schoolwide celebratory bulletins sent out in a flurry of excitement.

But Tellyer quickly moved past the fanfare to prepare for next year.

“I brought Mr. Allen back to speak to all secondary Poetry Out Loud students, including middle school, during homeroom,” Tellyer said. “I had current Poetry Out Loud students pick their poems they want to recite for next year. And I talked to incoming high school students about joining Poetry Out Loud and working to rehearse and participate in the schoolwide competition.”

“I want us to keep our eye on our larger goal to really continue building a culture passionate about arts and uplifting community voices,” Tellyer concluded. “Poetry is one of the oldest–if not the oldest–art form in human history. It was originally an oral tradition passed down from generation to generation. Some of our humanity’s stories and mythologies were memorized, set to music, and shared through the mode of verse. In some way, we are trying to build upon an ancient tradition, a deeply rooted human need for storytelling in one of the most natural forms of communication–poetry. But I also believe in a profound, metaphorical way that we are poetry itself. Our lives have a rhythm, a sequence, a meter, a pattern. In that way, poetry comes from our very heartbeat, our soul. I hope we can keep sharing that profound, thousands-year-old tradition with our school community and even others outside our school. I want our people to live life like a poem.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Norton Science & Language Academy. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.